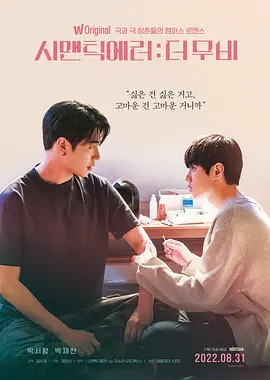

工学院的风云人物张宰英(朴栖含 饰),是个拥有模特儿好身材和脸蛋的视觉设计系大四生,成绩优越的边缘人秋尚宇(朴宰灿 饰),则是机械科的大三生,逻辑能力绝佳却有点书呆子。个性截然不同的两个人,却阴错阳差一起制作手游,张宰英对于秋尚宇来说,就像是电脑程式中的BUG错误指令,一场甜蜜的校园爱情就此展开。根据剧版重新剪辑的电影版将8集内容合在一起,再加上未公开视频一起制作。

亲属称谓【称呼“哥哥”】

在韩国电影《语义错误》中,“哥哥”这一称呼不仅是一种对亲属的称谓,也在韩国文化中具有深刻的社会和情感意义。这种称呼广泛用于家庭成员、朋友甚至较为亲密的非亲属之间,体现了韩国社会对年龄、辈分和社会关系的高度敏感性。我们可以从以下几个方面探讨这一现象:

1. 家庭与社会中的年龄和辈分文化

韩国社会高度重视年龄和辈分,这在语言中表现得尤为突出。称呼“哥哥”是基于年龄和性别的礼貌表达,通常用于女性对年长男性的称呼。这种称谓不仅体现了对年长者的尊重,也强调了社会等级的存在。这种文化源于儒家思想的影响,儒家强调“长幼有序”,即在家庭和社会关系中,年龄和辈分是一种天然的权威来源。

跨文化比较:

在西方文化中,如美国,亲属称谓更倾向于基于家庭关系本身,而非强调辈分。例如,兄长通常被直接称为名字或昵称,少有体现年龄优越感的专门称谓。

相比之下,在其他受到儒家文化影响的地区,如中国,“哥哥”的称谓也存在,但其使用场景和对等级的强调程度相对较低。

2. 情感纽带的强化功能

称呼“哥哥”不仅是语言习惯,也是一种情感表达。在《语义错误》中,这种称呼常常带有亲密和依赖的意味,表现了发出者对被称呼者的情感认同与信赖。在韩国文化中,这种称呼可以用于加深人际关系中的亲密感,即使是在非亲属关系中,也可以通过称呼“哥哥”来表达一种类似家庭关系的情感归属。

跨文化比较:

在某些文化中,情感表达更为直接,如西方文化中常使用直接语言或身体接触表达情感,而韩国文化倾向于通过礼貌称谓、间接方式表达内心的感受。

这种称呼对陌生文化者可能显得过于亲密,但在韩国,这是对关系认同和情感支持的一种礼仪性表现。

3. 非亲属场景中的灵活性

在韩国,称呼“哥哥”不仅限于血缘关系,还可以适用于熟人甚至是朋友之间,尤其在年长男性和年轻女性的关系中。通过这种称谓,可以自然地建立一种轻松、非正式但又带有尊敬的互动关系。这种做法反映了韩国文化中的“关系中心”思维,即通过称谓的使用不断强化人与人之间的联系。

跨文化比较:

在许多西方文化中,关系的建立更多依靠共同兴趣或对话内容,而不是通过固定称谓来体现。韩国文化的这种称谓灵活性可能会让外国人感到困惑,甚至误解为一种关系的实际亲密度高于真实情况。

In the Korean movie Semantic Error, the term “oppa” (哥哥, meaning “older brother”) is not just a familial title but carries profound social and emotional significance in Korean culture. This term is widely used for family members, friends, and even close non-relatives, reflecting the cultural emphasis on age, hierarchy, and relationships. The phenomenon can be analyzed from the following perspectives:

1. Cultural Significance of Age and Hierarchy

Korean society places great importance on age and hierarchy, which is particularly evident in its language. The term "oppa" is a respectful way for younger women to address older men, emphasizing not only respect for elders but also the inherent social hierarchy. This cultural norm is rooted in Confucianism, which stresses the order of relationships (“long-you-you-xu”), where age and seniority represent natural sources of authority.

Cross-cultural comparison:

In Western cultures like the U.S., familial titles tend to focus solely on the familial relationship without emphasizing hierarchy. For example, older brothers are often called by their first names or nicknames, with little reference to their seniority.

In other Confucian-influenced cultures like China, the term for “older brother” also exists but is less emphasized in daily interactions, and the hierarchy it signifies is less pronounced.

2. Reinforcement of Emotional Bonds

Using the term "oppa" is not merely a linguistic habit but an emotional expression. In Semantic Error, this term often conveys intimacy and reliance, reflecting the speaker’s emotional recognition and trust toward the person being addressed. In Korean culture, such terms serve as tools to strengthen interpersonal bonds, even in non-familial relationships, by creating a sense of familial connection.

Cross-cultural comparison:

In some cultures, emotional expressions are more direct, such as through explicit language or physical gestures common in Western contexts. Korean culture, however, tends to use respectful terms and indirect expressions to convey emotional depth.

To outsiders, such terms might seem overly intimate or confusing, but within Korean norms, it is a formalized way to express relational acknowledgment and emotional support.

3. Flexibility in Non-Familial Contexts

In Korea, calling someone "oppa" is not confined to blood relations but extends to acquaintances or friends, particularly when a younger female interacts with an older male. This flexible usage helps establish a casual yet respectful interaction. This practice reflects the relationship-oriented mindset of Korean culture, where terms of address continually reinforce interpersonal connections.

Cross-cultural comparison:

In many Western cultures, relationships are built more on shared interests or dialogue rather than fixed titles. The flexible use of titles like “oppa” in Korea may confuse outsiders, who might misinterpret it as signaling a higher level of intimacy than actually exists.

Conclusion

The use of “哥哥” (oppa) in Semantic Error exemplifies the intricate layers of social hierarchy, emotional expression, and relational thinking in Korean culture. Understanding the cultural context of such terms provides valuable insights into how relationships and identities are constructed and navigated in Korea. Moreover, it highlights the cultural nuances that can lead to misunderstandings or enrich intercultural interactions.

准时【不守时间的人不靠谱吧?】

在韩国电影《语义错误》中,守时被认为是一个重要的个人品质,而“不守时间”通常会被视为不可靠的表现。这一现象反映了韩国文化对时间管理、责任感以及社会关系的重视。我们可以从以下几个方面分析这一文化现象:

1. 时间观念与社会文化

韩国社会高度重视时间管理,这与韩国经济发展的历史和文化背景密切相关。韩国经历了快速工业化的进程,为了在有限的时间内完成任务,人们逐渐形成了强烈的时间意识。守时不仅是一种礼仪,更是一种效率和责任感的体现。不守时则会被认为是对他人时间的不尊重,甚至是对社会规则的违反。

跨文化比较:

在德国、日本等时间导向型文化中,守时被视为基本礼貌,人们会严格按照时间计划行事。

与此相对,在一些关系导向型文化(如拉丁美洲或中东),时间观念相对灵活,人们可能更看重人与人之间的互动,而非严格的时间管理。

2. 守时与人际关系的信任

守时不仅是一种行为规范,更与人际关系中的信任感密切相关。在《语义错误》中,如果一个人不守时,他可能被认为是没有责任感或缺乏承诺,这会影响到他在团队或社交中的可信度。韩国文化强调集体主义,在这样的社会中,个人的不守时行为可能被解读为对整个群体利益的忽视,从而削弱其社会关系中的信誉度。

跨文化比较:

在一些西方国家,如美国,虽然守时也是一种美德,但人们可能更倾向于将其视为个人习惯,而非判断整体可靠性的标准。

在关系导向型文化中,不守时可能不会引起强烈的负面评价,尤其是在信任已经建立的情况下。

3. 时间管理与职业伦理

在职业环境中,守时是职业素养的重要组成部分。在韩国职场文化中,守时被视为对工作的尊重,也是职业能力的基本体现。电影中主角之间的冲突部分源于时间管理的不一致,这反映了守时与职业伦理之间的紧密联系。不守时可能被认为是缺乏敬业精神或不够专业,从而影响职业发展。

跨文化比较:

在英国或加拿大等国家,守时在商业场合尤为重要,但在私人场合可能相对宽松。

在一些地区(如印度或非洲部分国家),时间的弹性较大,守时可能并非评价职业能力的核心标准。

In the Korean movie Semantic Error, punctuality is considered a vital personal quality, while being late is often seen as a sign of unreliability. This phenomenon reflects the cultural emphasis on time management, responsibility, and social relationships in Korea. This cultural trait can be analyzed from the following perspectives:

1. Time Orientation and Cultural Values

Korean society places great importance on time management, deeply rooted in the country’s historical and cultural context. During Korea’s rapid industrialization, efficient use of time became essential for accomplishing tasks within tight deadlines. Consequently, punctuality evolved into a marker of respect and responsibility. Being late, on the other hand, is often interpreted as a disregard for others' time and even as a violation of social norms.

Cross-cultural comparison:

In time-oriented cultures like Germany and Japan, punctuality is considered a fundamental courtesy, and people strictly adhere to schedules.

Conversely, in relationship-oriented cultures such as Latin America or the Middle East, time is viewed more flexibly, with interpersonal interactions prioritized over strict time adherence.

2. Punctuality and Trust in Relationships

Punctuality is not merely a behavioral norm but is closely tied to trust in interpersonal relationships. In Semantic Error, a person who is late might be perceived as irresponsible or lacking commitment, which could undermine their credibility in both team and social settings. Korean culture emphasizes collectivism, where an individual’s failure to be punctual might be interpreted as neglecting the group’s interests, thereby damaging trust.

Cross-cultural comparison:

In some Western countries, such as the U.S., while punctuality is valued, it is often regarded more as a personal habit than a defining measure of overall reliability.

In relationship-oriented cultures, being late might not provoke strong negative reactions, especially if trust has already been established.

3. Time Management and Professional Ethics

In professional environments, punctuality is an integral part of workplace ethics. In Korean workplace culture, being on time is seen as a sign of respect for the job and a fundamental indicator of professionalism. Conflicts in the movie often arise from differences in time management, highlighting the connection between punctuality and work ethics. Being late might be perceived as a lack of dedication or professionalism, potentially hindering career advancement.

Cross-cultural comparison:

In countries like the U.K. or Canada, punctuality is critical in business settings but may be more relaxed in social contexts.

In other regions, such as India or parts of Africa, time tends to be more flexible, and punctuality may not always be a primary indicator of professional competence.

Conclusion

Punctuality in Semantic Error serves as a lens through which we can understand the cultural importance of time management in Korea. It highlights the connection between punctuality, trust, and professionalism. Understanding these cultural nuances can facilitate better communication and cooperation in cross-cultural interactions while also shedding light on how different societies prioritize and interpret time.

礼物【当面打开?】

校园霸凌【趁学弟睡觉往脸上画图,让其摘掉帽子】

在韩国电影《语义错误》中,校园霸凌现象被通过主角之间的互动细节呈现,例如趁学弟睡觉时在其脸上画图,以及试图强迫他摘掉帽子。这些行为虽然表面上可能被视为“玩笑”,但却反映了校园霸凌的深层文化含义。我们可以从以下几个方面来分析这一现象:

1. 校园霸凌的文化背景

在许多文化中,校园霸凌都是一种普遍的现象,往往与青少年时期的权力动态有关。在韩国社会中,由于其高度集体化的教育环境和严格的等级制度,校园霸凌可能更多地体现为高年级对低年级或群体对个体的权力压迫。在电影中的例子中,学弟的被动反应以及试图保护自己的行为(如戴帽子)表明他处于一种无力反抗的弱势地位。

跨文化比较:

在韩国,这种霸凌行为可能源于传统的长幼有序观念,这种观念在校园中经常演化为高年级对低年级的支配。

相比之下,在一些以个体主义为主的国家(如美国),霸凌的形式可能更多地涉及言语或网络攻击,主要基于社交地位或个人特点,而非等级关系。

2. “玩笑”与权力的不平衡

校园霸凌行为常常被以“玩笑”之名掩盖,尤其是在团体文化较强的社会中。这种行为表面上被包装为“幽默”或“增进感情”,但实际上却是一种利用权力优势让对方感到尴尬或屈辱的方式。在《语义错误》中,趁学弟睡觉画图和摘帽子的行为不仅侵犯了他的个人边界,还剥夺了他维护自尊的能力。

跨文化比较:

韩国文化中的集体主义可能使个体更难公开反对这种行为,因为害怕被排斥或孤立。

在欧美国家,个人边界的观念更为强烈,这种行为可能会引发更快的反抗或直接诉诸外部帮助。

3. 社会压力与受害者的应对

受害者在面对霸凌时的应对方式,也受到文化背景的深刻影响。在韩国文化中,由于对和谐和群体认同的重视,受害者通常选择忍耐而非对抗,甚至可能通过行为改变(如摘掉帽子)来迎合施压者。然而,这种行为的长期后果可能是对自我认知的负面影响,以及进一步的社会孤立。

跨文化比较:

在一些国家,受害者可能更倾向于诉诸家长、学校或法律资源寻求帮助,这种文化对个体权利的重视可能缓解霸凌行为的长期影响。

在强调面子文化的社会中,受害者可能会选择隐藏遭遇,避免被视为“软弱”。

4. 应对校园霸凌的集体责任

校园霸凌不仅是个体行为,也反映了一个社会对教育环境和人际关系的整体态度。在韩国社会中,家长、教师和同学的反应在很大程度上决定了霸凌的严重性以及是否能被有效遏制。如果社会对“玩笑”与“霸凌”界限的认识不清,霸凌行为可能被进一步强化或正常化。

In the Korean movie Semantic Error, school bullying is depicted through subtle interactions between the characters, such as drawing on a junior’s face while he sleeps or pressuring him to remove his hat. While these actions may superficially appear as “jokes,” they reveal deeper cultural implications of bullying. This phenomenon can be analyzed through the following lenses:

1. Cultural Context of School Bullying

School bullying is a widespread phenomenon across cultures and often reflects the power dynamics among adolescents. In Korean society, the highly collectivist educational environment and strict hierarchical structure often exacerbate bullying, with seniors exerting dominance over juniors or groups targeting individuals. In the movie, the junior’s passive response and attempts to protect himself (e.g., wearing a hat) indicate his powerless position.

Cross-cultural comparison:

In Korea, such bullying behaviors may stem from traditional values of age-based hierarchy, which often translate into seniority dominance in schools.

In contrast, in individualistic countries like the U.S., bullying might more frequently take the form of verbal or cyber aggression based on social status or personal traits, rather than hierarchical dynamics.

2. “Jokes” and Power Imbalance

Bullying is often disguised as “jokes,” particularly in collectivist cultures. Such behavior is framed as “humor” or “bonding” but serves as a way to embarrass or humiliate the victim through a power imbalance. In Semantic Error, actions like drawing on the junior’s face or pressuring him to remove his hat not only violate his personal boundaries but also strip him of the ability to maintain his dignity.

Cross-cultural comparison:

In Korea’s collectivist culture, individuals may be reluctant to openly resist such actions for fear of social exclusion or rejection.

In Western cultures, where personal boundaries are more strongly emphasized, such behavior might provoke quicker resistance or a direct appeal for external intervention.

3. Social Pressure and Victim Coping Mechanisms

The way victims respond to bullying is deeply influenced by cultural norms. In Korean culture, the emphasis on harmony and group conformity often leads victims to endure rather than confront bullying. They may even alter their behavior (e.g., removing the hat) to appease their aggressors. However, the long-term consequences of such actions may include negative self-perception and further social isolation.

Cross-cultural comparison:

In some countries, victims might be more likely to turn to parents, schools, or legal systems for help, reflecting a cultural emphasis on individual rights that could mitigate the lasting effects of bullying.

In face-saving cultures, victims may hide their experiences to avoid being perceived as “weak.”

4. Collective Responsibility in Addressing School Bullying

School bullying is not just an individual behavior but also reflects societal attitudes toward educational environments and interpersonal relationships. In Korean society, the reactions of parents, teachers, and peers significantly influence the severity of bullying and whether it can be effectively addressed. If the distinction between “jokes” and “bullying” is unclear, such behaviors may become normalized or even encouraged.

Conclusion

The bullying depicted in Semantic Error illustrates the complex interplay between cultural values, power dynamics, and individual agency. Understanding these cultural nuances not only sheds light on the challenges faced by victims in Korean society but also highlights the importance of fostering awareness and intervention mechanisms in educational settings. Addressing bullying requires collective effort to redefine boundaries between humor and harm and to create a more inclusive and respectful social environment.

敬语的使用

在韩国电影《语义错误》中,敬语的使用成为角色互动的一个显著特征,既表现了韩国文化中的等级意识,也体现了语言与社会关系的深度关联。敬语是韩国语的一大特色,它不仅是一种语言形式,更是一种反映社会结构的文化现象。

1. 敬语的文化背景

在韩国,敬语的使用有严格的社会规范。它与年龄、地位、职业及亲疏关系密切相关。通过敬语的使用,讲话者可以明确表示对听者的尊重,同时维护社会关系的和谐。例如,在电影中,角色之间的对话往往因身份和关系的不同而选择不同的语调与措辞。如果面对年长者或社会地位更高者,使用敬语是必需的。而如果是与同龄人或亲密朋友交流,则可使用更随意的非敬语形式。

这种语言现象体现了韩国文化中的等级观念,即“长幼有序”和对社会秩序的重视。敬语的使用不仅传递信息,还维持了社会规范和关系的平衡。

2. 语言的社会功能

敬语在韩国文化中的核心功能不仅限于表达礼貌,还包括建立和维系人际关系。在《语义错误》中,主角之间的语言选择反映了他们关系的演变。例如,当两个角色从初次见面逐渐熟悉后,可能会从敬语转变为非敬语,这种语言上的变化象征着关系的亲密化。相反,如果角色间因冲突而疏远,他们可能重新使用敬语以重新拉开社会距离。

3. 跨文化对比

在其他文化中,类似的敬语体系可能不如韩国语这样复杂。例如,英语中的“you”既可用于朋友也可用于长辈,没有明确的语法形式区分尊卑关系。相比之下,汉语虽然也有类似的尊敬表达(如“您”),但敬语体系较为简单,更多依赖语气和称谓。

这种差异可能导致跨文化交流中的误解。例如,一位非韩语母语者在与韩国人交流时,若不使用适当的敬语,可能被认为是无礼的,而这在他/她自己的文化中可能完全不是问题。

4. 现代社会的影响

随着韩国社会逐渐现代化,特别是年轻一代的影响,敬语的使用正发生微妙的变化。例如,职场和日常生活中的对话可能变得更加随意,尤其是在互联网和社交媒体交流中。然而,敬语作为韩国文化的重要组成部分,其核心功能仍然未变:表达尊重与维护社会和谐。

In the Korean movie Semantic Error, the use of honorifics is a prominent feature of character interactions, reflecting the hierarchical awareness in Korean culture and the deep connection between language and social relationships. Honorifics in Korean are not just a linguistic form; they are a cultural phenomenon that mirrors societal structures.

1. Cultural Background of Honorifics

In Korea, the use of honorifics is governed by strict social norms and is closely tied to factors such as age, status, profession, and the nature of relationships. By using honorifics, speakers can explicitly convey respect and maintain harmony in social interactions. For instance, in the movie, the characters’ dialogue varies depending on their respective identities and relationships. When addressing elders or individuals of higher status, the use of honorifics is obligatory. Conversely, informal speech is more common among peers or close friends.

This linguistic phenomenon reflects the hierarchical principles in Korean culture, emphasizing the importance of age order and social structure. The use of honorifics serves not only as a means of communication but also as a tool to uphold social norms and balance relationships.

2. Social Functions of Language

The core function of honorifics in Korean culture goes beyond politeness to include the establishment and maintenance of interpersonal relationships. In Semantic Error, the characters’ choice of speech styles often signifies the evolution of their relationships. For example, as two characters become more familiar with each other, they may transition from honorifics to informal speech, symbolizing a closer bond. Conversely, during conflicts or growing distance, they might revert to honorifics to reestablish social boundaries.

3. Cross-Cultural Comparison

In other cultures, comparable honorific systems may not be as complex as in Korean. For instance, English employs the single pronoun “you” for both friends and elders, without distinct grammatical forms to denote status differences. In contrast, while Mandarin Chinese has some respectful expressions (e.g., 您 nín for “you”), its honorific system is simpler and relies more on tone and terms of address.

Such differences can lead to misunderstandings in cross-cultural communication. For example, a non-native Korean speaker might unintentionally come across as rude if they fail to use the appropriate honorifics, even though such behavior might be entirely acceptable in their own culture.

4. Impact of Modern Society

As Korean society modernizes, especially under the influence of younger generations, the use of honorifics is undergoing subtle changes. For instance, workplace and everyday conversations may become more casual, particularly in digital communication on social media. However, honorifics remain a vital aspect of Korean culture, retaining their core function of expressing respect and preserving social harmony.

Conclusion

The use of honorifics in Semantic Error highlights the cultural importance of linguistic choices in Korean society. By analyzing these practices, we can better understand how language acts as a bridge between individual expression and societal norms. Furthermore, appreciating the nuances of honorifics is crucial for fostering successful cross-cultural communication and mutual respect.

韩国的酒文化【劝酒】

在韩国电影《语义错误》中,劝酒的情节突出了韩国酒文化的独特性。劝酒不仅是酒桌上的互动方式,更是一种深植于韩国文化中的社交现象,反映了集体主义价值观、等级意识和人际关系的重要性。

1. 韩国酒文化的背景

韩国酒文化可以追溯到悠久的历史,它在现代社会中依然扮演着重要角色。在传统的韩国社会中,酒不仅是一种饮品,更是一种连接情感、促进交流的媒介。无论是在家庭聚会、朋友聚餐还是商务场合中,喝酒都是拉近关系和增强团体归属感的方式。劝酒作为酒文化的一部分,是体现热情、建立信任的常见行为。

2. 劝酒的社会功能

在韩国文化中,劝酒不仅是一种礼节,更是一种展示集体主义文化的表现。通过劝酒,参与者可以表达对对方的友善和认可。特别是在职场和商务场合,接受劝酒甚至被视为一种对团体和上级的尊重。例如,在《语义错误》中,角色之间的劝酒行为不仅体现了同事之间的亲近感,也反映了韩国文化中的等级观念。年长者或地位较高者通常会主动劝酒,而年轻人或地位较低者接受劝酒则表示对长辈的尊敬。

3. 文化中的潜在问题

尽管劝酒是一种文化现象,但它也可能带来一定的文化冲突和误解。对于非韩国文化背景的人来说,强迫性劝酒可能被视为一种压力,甚至冒犯个人意愿。特别是在现代社会,年轻一代对个人隐私和选择的尊重意识增强,过度劝酒可能会引发不满或拒绝。

4. 现代视角下的劝酒文化

随着时代的变化,韩国酒文化也在逐渐转变。年轻一代越来越重视个人边界和健康问题,劝酒的行为也开始淡化。在许多场合,“尊重选择”成为一种新趋势。例如,在社交场合中,选择不喝酒的人可以用软性饮品代替,而不会遭到过多的质疑。这种转变体现了传统与现代价值观之间的平衡。

5. 跨文化比较

相比之下,在西方文化中,喝酒更倾向于个人选择,劝酒的行为相对较少,强调尊重个人意愿。中日文化中也有类似的酒桌文化,但程度和形式有所不同。例如,中国的酒桌文化中更注重“感情深,一口闷”的仪式感,而日本则以“倒酒礼仪”为主,重视酒桌上的细节礼仪。韩国的劝酒文化在亚洲中显得更为直接,尤其是在表达情感和增进关系方面。

In the Korean movie Semantic Error, scenes involving encouraging others to drink (known as "gwonjeol", 권주) highlight the unique characteristics of Korean drinking culture. This practice is more than just table etiquette; it is a deeply ingrained social phenomenon that reflects collectivist values, hierarchical awareness, and the importance of interpersonal relationships in Korean society.

1. Background of Korean Drinking Culture

Korea’s drinking culture has a long history and continues to play a significant role in modern society. Traditionally, alcohol is not merely a beverage but a medium for fostering emotional bonds and promoting interaction. Whether at family gatherings, social dinners with friends, or professional meetings, drinking is often seen as a way to strengthen relationships and enhance group belonging. Encouraging others to drink is a key aspect of this culture, symbolizing warmth and trust.

2. Social Functions of Encouraging Drinking

In Korean culture, the act of encouraging others to drink is both a gesture of politeness and a demonstration of collectivist values. By doing so, participants express friendliness and recognition toward others. Especially in professional and business settings, accepting a drink is often regarded as a sign of respect for the group or superiors. For example, in Semantic Error, characters engaging in such drinking practices highlight the closeness of their relationships and the hierarchical nuances of Korean culture. Typically, older or higher-ranking individuals take the lead in offering drinks, while younger or lower-ranking individuals accept the offer as a mark of respect.

3. Potential Cultural Issues

While encouraging drinking is a cultural norm in Korea, it can lead to misunderstandings or conflicts, especially in cross-cultural contexts. Non-Koreans may perceive coercive drinking as undue pressure or even an infringement on personal autonomy. Moreover, in modern society, younger generations place greater emphasis on respecting personal boundaries and choices, making excessive encouragement to drink potentially unwelcome.

4. A Modern Perspective on Drinking Culture

With changing times, Korean drinking culture is evolving. Younger generations are increasingly prioritizing personal boundaries and health, leading to a decline in traditional drinking rituals. Respecting individual choices has become a growing trend in many social contexts. For instance, people who choose not to drink can now opt for non-alcoholic beverages without facing excessive questioning. This shift reflects a balance between traditional and modern values.

5. Cross-Cultural Comparison

In contrast, Western cultures generally emphasize individual choice when it comes to drinking, with minimal encouragement involved. In Chinese and Japanese cultures, there are also distinct drinking customs, though they differ in degree and form. For example, Chinese drinking culture often emphasizes toasts with a sense of ceremonial bonding, while Japanese customs focus on meticulous etiquette, such as pouring drinks for one another. Among Asian cultures, Korea’s drinking culture stands out for its directness, especially in its use of drinking to express emotions and deepen relationships.

Conclusion

Korean drinking culture, as depicted in Semantic Error, serves as a fascinating lens through which to explore the interplay between tradition, social hierarchy, and evolving modern values. Understanding this phenomenon is crucial for appreciating Korea’s cultural landscape and navigating its social norms effectively, particularly in cross-cultural contexts. Respecting boundaries while honoring traditions is key to bridging cultural gaps.

对恋爱婚姻的看法

对敌手的怀疑【不喜欢的人给灌咖啡,引起怀疑】

在韩国电影《语义错误》中,主人公对不喜欢的人主动递上的咖啡感到怀疑,这种行为反映了一种微妙的人际心理和文化现象。作为一种跨文化的视角,可以将这一现象从以下几个方面进行分析。

1. 社会背景与文化特征

韩国文化中非常强调“内外有别”的观念,即在亲近和不亲近的人之间会有显著的互动差异。主动提供饮品或食物通常被视为一种友好的社交行为,而当这种行为来自于不喜欢或不信任的人时,接受者可能会产生防备心理。这种心理根植于韩国文化中注重关系网和情感纽带的特性,陌生或敌对的关系中,过于热情的行为可能被解读为别有用心。

2. 人与人之间的信任机制

在很多集体主义文化中,人际关系和信任往往是基于时间的积累与实际行为的证明。然而,对于交往较少或存在矛盾的人,信任往往是脆弱的,甚至缺失。在这种情况下,对方的善意行为反而可能引发怀疑,担心背后有隐含的目的。在《语义错误》中,这种不信任体现为对敌手“灌咖啡”行为的戒备。虽然表面上是好意,但基于既有矛盾和对人性的深层次解读,主人公的怀疑并非没有依据。

3. 跨文化的对比

相比之下,西方文化尤其是个体主义导向的国家中,人们可能会更加愿意接受来自“不喜欢的人”的善意行为,倾向于将其解读为缓和关系或试图建立桥梁。在日本等邻近国家中,类似的行为则可能更多被解读为遵守礼节,而不会被赋予太多情感色彩。相比之下,韩国文化对“敌我分明”的界定较为强烈,这也与其长期受儒家思想影响有关。

4. 现代化视角与心理学分析

在现代社会中,人与人之间的竞争压力和对他人动机的敏感度增加,尤其是在职场和校园等竞争环境中。这种现象从心理学角度也可以解释为“认知偏差”——由于对某人的负面情感,可能倾向于过度解读其行为的潜在动机。这种行为并不局限于韩国,但在文化中强调集体内关系和社会等级的国家中更为明显。

5. 影视作品中的文化符号

《语义错误》中这一细节不仅塑造了角色的个性,也反映了韩国文化中的复杂人际动态。这种文化符号让观众能够通过角色行为解读潜在的社会心理和文化价值,尤其是如何处理信任与怀疑之间的微妙平衡。

In the Korean movie Semantic Error, the protagonist's suspicion when offered coffee by someone they dislike reflects a nuanced interpersonal dynamic and cultural phenomenon. From a cross-cultural perspective, this behavior can be analyzed from several angles.

1. Social Context and Cultural Characteristics

Korean culture emphasizes the concept of "inside and outside" (내외), which differentiates between interactions with close versus distant individuals. Offering beverages or food is often seen as a friendly social gesture. However, when such an action comes from someone disliked or distrusted, it can trigger defensive reactions. This mentality is rooted in Korean culture, which places great importance on relational networks and emotional bonds. Overly friendly actions in adversarial relationships might be interpreted as having ulterior motives.

2. Trust Mechanisms in Interpersonal Relationships

In many collectivist cultures, trust and interpersonal connections are built over time and through consistent actions. For individuals who have minimal interaction or harbor conflicts, trust is fragile or nonexistent. In such scenarios, acts of goodwill may raise suspicions about hidden agendas. In Semantic Error, this distrust manifests as wariness toward an "enemy" offering coffee. While seemingly benevolent, the protagonist's doubts stem from prior conflicts and deeper interpretations of the gesture.

3. Cross-Cultural Comparisons

In contrast, in Western cultures, particularly in individualistic societies, people may be more willing to accept acts of goodwill from someone they dislike, interpreting them as attempts to mend relationships or build bridges. In Japan, similar behavior might be viewed more neutrally as adherence to etiquette, without attaching significant emotional connotations. Korean culture, however, often emphasizes clearer distinctions between allies and adversaries, a perspective shaped by its Confucian heritage.

4. Modern Perspectives and Psychological Insights

In contemporary society, increased competition and heightened sensitivity to others' motives contribute to such suspicion, especially in high-stakes environments like workplaces or schools. From a psychological standpoint, this phenomenon could be explained as "cognitive bias"—a tendency to overinterpret the motives of individuals with whom one shares negative sentiments. While not unique to Korea, this behavior is more pronounced in cultures that stress in-group relationships and social hierarchies.

5. Cultural Symbols in Media

This particular scene in Semantic Error not only highlights the character’s personality but also sheds light on the intricate interpersonal dynamics in Korean culture. This cultural symbol allows audiences to decode the underlying social psychology and values, particularly the delicate balance between trust and suspicion.

Conclusion

The suspicion of an adversary’s goodwill gesture, as depicted in Semantic Error, serves as a microcosm of Korean interpersonal and cultural dynamics. It illustrates the importance of relational context and cultural norms in shaping behaviors and perceptions. For outsiders, understanding this phenomenon provides valuable insights into navigating trust and relationships in Korean society.

作弊是不公平的【如果记不住就写手上,被拒绝,因为不公平】

在韩国电影《语义错误》中,关于考试作弊的情节展现了学生之间对公平性和诚实的重要价值观。这种文化现象在韩国乃至许多其他社会中,都能引起观众的共鸣。我们可以从以下几个方面分析这一现象。

1. 公平性的社会价值

作弊行为本质上破坏了“公平竞争”的原则。韩国社会高度重视通过个人努力获得成功的观念,这与韩国儒家文化强调正直和自律的传统密不可分。在教育和职场等高度竞争的环境中,公平性被视为确保机会平等的基础。学生之间对作弊的敏感,反映了他们对公平竞争环境的渴望。

2. 群体道德与信任机制

在集体主义文化中,个人行为对群体的影响被放大。作弊不仅是一种个人行为,也可能被视为对整个班级、学校甚至社会道德体系的威胁。拒绝作弊不仅体现了学生对自身价值的捍卫,也反映了对群体伦理和信任体系的维护。这种强烈的责任感是韩国文化中的一大特征。

3. 跨文化视角:对作弊的态度差异

虽然在大多数文化中,作弊都被认为是不道德的,但其严重程度和对作弊的反应却有所不同。例如,在一些竞争压力较大的文化中,作弊可能被某些人视为一种不得已的“策略”,但在韩国,因注重教育和诚信,作弊往往会引发更强烈的道德谴责。相比之下,在一些西方个体主义文化中,作弊可能更多地被视为对个人价值观的挑战,而非对群体的威胁。

4. 教育体制与作弊现象

韩国教育系统以严格和竞争性著称,考试成绩对学生未来发展的影响极为深远。这种高压力的教育环境虽然可能在一定程度上促使某些学生寻找捷径,但总体来说,社会对作弊行为持零容忍态度。学生之间对作弊的拒绝,尤其是在《语义错误》中体现的拒绝帮他人作弊的行为,不仅是一种道德约束,也是一种对公平教育环境的坚守。

5. 影视中的文化隐喻

《语义错误》通过这一情节展现了韩国文化对诚实、努力和公平的推崇。这不仅有助于观众理解韩国学生的价值观,还反映了教育作为社会公正的基石所扮演的角色。电影中主角拒绝作弊的行为成为角色塑造的重要元素,同时也展现了韩国社会如何看待道德选择与个人诚信的关系。

In the Korean movie Semantic Error, a scene about cheating during exams highlights the importance of fairness and honesty among students. This cultural phenomenon resonates with audiences in Korea and many other societies. This can be analyzed from the following perspectives.

1. The Social Value of Fairness

Cheating fundamentally undermines the principle of fair competition. Korean society places great emphasis on achieving success through individual effort, a value deeply rooted in the Confucian traditions of integrity and self-discipline. In highly competitive environments like education and the workplace, fairness is seen as the cornerstone of equal opportunity. Students’ sensitivity toward cheating reflects their aspiration for a level playing field.

2. Group Morality and Trust Mechanisms

In collectivist cultures, individual behavior significantly impacts the group. Cheating is not merely a personal act; it is often perceived as a threat to the moral fabric of the class, school, or even society. Refusing to cheat reflects not only the student's commitment to personal integrity but also their dedication to preserving group ethics and trust. This sense of responsibility is a prominent feature of Korean culture.

3. Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Cheating

While cheating is universally deemed unethical, the severity of its perception and reactions to it vary across cultures. In some high-pressure environments, cheating might be viewed by certain individuals as a "necessary strategy." In Korea, however, where education and honesty are highly valued, cheating typically triggers stronger moral condemnation. By contrast, in some Western individualistic cultures, cheating might be seen more as a challenge to personal values than a threat to group harmony.

4. Educational System and Cheating

The Korean education system is renowned for its rigor and competitiveness, with exam performance playing a pivotal role in students’ future prospects. While this high-pressure environment might drive some students to seek shortcuts, the society as a whole maintains a zero-tolerance stance toward cheating. The refusal to cheat among students, as depicted in Semantic Error, particularly the act of refusing to help others cheat, demonstrates both moral restraint and a commitment to maintaining an equitable educational environment.

5. Cultural Metaphors in Film

Through this scene, Semantic Error portrays Korean culture's reverence for honesty, hard work, and fairness. This not only helps audiences understand the values held by Korean students but also highlights education’s role as a foundation of social justice. The protagonist's decision to refuse cheating becomes a crucial element of character development, showcasing how moral choices intersect with personal integrity in Korean society.

Conclusion

The rejection of cheating as depicted in Semantic Error serves as a microcosm of broader cultural values in Korea. It emphasizes the societal emphasis on fairness and the importance of individual integrity within collective systems. This understanding provides a lens for interpreting ethical dilemmas in educational contexts, both in Korea and beyond.

付钱算清楚【女同学想付咖啡钱,男同学归还,女同学找零】

在韩国电影《语义错误》中,关于咖啡付款的情节,展现了同学之间在金钱往来中精确计算的行为。这种现象反映了韩国文化中对经济责任、礼貌以及个人独立性的重视,也可以从多层次的跨文化角度来解读。

1. 经济责任与个人独立性

在韩国文化中,年轻人通常从大学时期开始注重培养经济独立性,避免成为他人的经济负担。在这段情节中,女同学坚持支付咖啡钱,反映了她对自己经济责任的承担,同时体现出一种自尊和独立意识。她不希望因为金钱问题给他人带来负担,而这在许多东亚文化中都具有共通性。

2. 礼貌与人际关系中的平等

韩国社会强调礼貌与关系中的平等。这种文化背景下,同学之间明确结算费用,可以避免不必要的尴尬和潜在的关系不平衡。女同学找零的行为,虽然看似琐碎,但表达了她希望保持人际交往中的对等关系,体现了一种对他人情感和社会规范的敏感性。

3. 性别与支付文化的互动

传统上,韩国文化中男士为女士支付费用的行为较为常见,但随着社会观念的转变,尤其在年轻一代中,性别角色逐渐趋于平等。女同学坚持付款,反映了她对传统性别期待的某种拒绝。她用行动表明,自己的经济能力和社会角色并不依赖于男性的支持,这种态度代表了当代韩国女性的一种新型自我认同。

4. 跨文化对比:支付行为的差异

在一些西方文化中,同学或朋友之间常采用“分摊制”(split the bill),而在某些集体主义文化中,互请或轮流付款则更为常见。在韩国,明确结算的习惯则介于两者之间。一方面,这种行为反映了现代社会中个人权责分明的特点;另一方面,也与传统文化中避免“不欠人情”的理念相契合。

5. 影视中的文化隐喻

这段剧情不仅是简单的生活细节,还隐喻了当代韩国社会对经济伦理、性别平等以及人际关系的新思考。通过女同学的举动,观众能够更深刻地体会到年轻一代如何在传统与现代之间寻找平衡点。

In the Korean movie Semantic Error, a scene involving the payment for coffee illustrates the meticulousness in financial transactions among classmates. This phenomenon reflects Korea’s cultural emphasis on financial responsibility, politeness, and individual independence, which can be analyzed from various cross-cultural perspectives.

1. Financial Responsibility and Individual Independence

In Korean culture, young people are encouraged to develop financial independence, often starting from their university years, to avoid being a burden to others. In this scene, the female classmate’s insistence on paying for the coffee demonstrates her sense of financial responsibility, along with her self-respect and independence. She does not want to impose a financial burden on others, a value shared by many East Asian cultures.

2. Politeness and Equality in Interpersonal Relationships

Korean society places high importance on politeness and maintaining equality in relationships. By clearly settling the payment, the classmates avoid unnecessary awkwardness or potential imbalances in their relationship. The female classmate’s act of giving exact change, while seemingly trivial, conveys her intention to maintain an equitable and respectful relationship, reflecting an awareness of others’ feelings and societal norms.

3. Gender Dynamics and Payment Culture

Traditionally, Korean culture often expects men to pay for women, but this norm is shifting with changing societal values, particularly among the younger generation. The female classmate’s insistence on paying challenges traditional gender expectations. Her action signifies her independence and rejects reliance on male financial support, representing a new form of self-identity embraced by modern Korean women.

4. Cross-Cultural Comparison: Payment Behaviors

In some Western cultures, it is common for friends or classmates to "split the bill," while in some collectivist cultures, treating others or taking turns to pay might be the norm. In Korea, the practice of settling payments precisely lies between these extremes. On one hand, it reflects modern individualistic values of clear accountability; on the other hand, it aligns with the traditional notion of avoiding indebtedness to others.

5. Cultural Metaphors in Film

This scene is more than a simple depiction of daily life; it symbolizes broader cultural themes of economic ethics, gender equality, and evolving interpersonal dynamics in contemporary Korea. Through the female classmate’s actions, the audience gains deeper insights into how the younger generation seeks a balance between tradition and modernity.

Conclusion

The payment interaction in Semantic Error exemplifies Korean cultural values and provides a window into how financial practices reflect broader societal trends. It highlights the importance of responsibility, equality, and evolving gender roles, offering valuable insights for cross-cultural understanding.

亲属称谓【关系好时叫“哥哥”,关系不好时不让叫】

不要随便身体接触

谁买单?【“你叫我来打球的,你买单”】

在韩国电影《语义错误》中,关于“谁买单”的对话,展现了韩国文化中关于支付责任的潜在规范和社会期待。这种文化现象可以从以下几个方面进行分析,既体现了韩国文化中的人际互动规则,也反映了现代年轻人对传统礼仪的调整和回应。

1. 邀请者支付的文化惯例

在韩国文化中,传统上由发出邀请的一方承担费用是一种常见的礼仪。这种习惯基于集体主义文化中对关系维护的高度重视。发出邀请者被认为承担起了组织活动的责任,通过支付费用表达对被邀请者的感谢。这种做法不仅避免了经济上的分歧,也是一种对关系和谐的维护。

2. 地位与关系中的权力平衡

韩国文化强调人际关系中的等级与礼节,因此支付责任也与双方的地位或关系性质密切相关。例如,在长辈与晚辈、上司与下属的互动中,通常由长辈或上司支付费用,以示关怀和权威。而在同龄人或朋友之间,支付规则则更加灵活,常与具体情境和邀请动机相关。

3. 现代年轻人对传统支付文化的挑战

近年来,随着社会个体主义倾向的增加,年轻一代在支付方面更强调公平性和个体责任。例如,在电影中,“你叫我来打球的,你买单”的说法不仅遵循了邀请者支付的传统,也折射出年轻人对直接沟通和关系平等的追求。这种方式减少了不必要的猜测或负担,体现了效率与实用性。

4. 跨文化对比:支付规则的差异

韩国支付文化与许多其他国家存在差异。在一些西方国家,比如美国,常见的方式是“AA制”(各自分摊费用),强调独立性和平等。而在某些其他东亚文化中,轮流支付或由地位较高者支付则更为普遍。韩国的支付习惯处于传统与现代之间的过渡状态,既体现了关系导向,又逐步接纳平等与个人主义的观念。

5. 支付文化的社会意义

支付行为不仅是经济活动,也是社会互动的一部分。在韩国文化中,通过支付行为传递感情、表达谢意或建立关系的意义远超金钱本身。这一现象在电影中通过对话的简单呈现,让观众感受到支付文化的复杂性以及其背后的社会规范。

In the Korean movie Semantic Error, the dialogue about "who pays" highlights the implicit norms and societal expectations around payment responsibilities in Korean culture. This phenomenon reflects the rules of social interaction in Korea and reveals how modern youth are adjusting traditional etiquette to fit their preferences.

1. The Cultural Norm of the Inviter Paying

Traditionally in Korean culture, the person who extends the invitation is expected to cover the cost. This practice is rooted in the collectivist value of relationship maintenance. The inviter is seen as taking responsibility for organizing the activity and expresses gratitude to the invitee by paying. This custom not only avoids economic disputes but also serves to maintain social harmony.

2. Hierarchy and Power Dynamics in Relationships

Korean culture places significant emphasis on hierarchy and etiquette in interpersonal relationships. Payment responsibility often aligns with the status or nature of the relationship. For example, in interactions between seniors and juniors or superiors and subordinates, the senior or superior typically pays to show care and authority. Among peers or friends, however, the rules are more flexible and often depend on the specific context and intent behind the invitation.

3. Modern Youth Challenging Traditional Norms

In recent years, with the growing trend toward individualism, younger generations have started emphasizing fairness and personal responsibility in payment. In the movie, the statement, "You invited me to play basketball, so you pay," adheres to the traditional norm of the inviter paying while also reflecting a preference for straightforward communication and equality. This approach minimizes unnecessary guesswork or burden, aligning with a more pragmatic and efficient mindset.

4. Cross-Cultural Comparison: Payment Practices

Korean payment culture differs from many other countries. In Western countries like the United States, the "split the bill" approach is common, emphasizing independence and equality. In other East Asian cultures, rotating payments or the higher-status individual covering the cost is more typical. Korean practices lie at the intersection of traditional and modern values, blending relationship-oriented customs with growing acceptance of equality and individualism.

5. The Social Significance of Payment Culture

Payment behavior in Korea is not merely an economic activity but a critical part of social interaction. Through payment, individuals convey emotions, express gratitude, or strengthen relationships, with the significance often exceeding the monetary value itself. In the movie, this simple dialogue about payment highlights the complexities of payment culture and the societal norms it represents, offering the audience a deeper understanding of its multifaceted role.

Conclusion

The discussion of payment responsibilities in Semantic Error provides valuable insight into Korean cultural values. It illustrates how financial interactions are a reflection of broader societal dynamics, balancing tradition and modernity, and highlights the nuanced role of payment in building and maintaining social relationships.

看到纹身就联想到小混混

在韩国电影《语义错误》中,角色对纹身的负面联想,特别是将其与“小混混”联系起来,反映了韩国社会对纹身的传统偏见和社会文化背景。这种现象可以从以下几个方面进行分析:

1. 纹身的历史与文化背景

纹身在韩国的历史渊源复杂。传统上,纹身在韩国社会常与犯罪或边缘化群体联系在一起。在过去,纹身被视为帮派成员的象征,用于标明身份或表达对组织的忠诚。这种历史记忆使得纹身在公众眼中具有负面含义,与主流文化格格不入。

2. 儒家文化的道德与身体观念

韩国深受儒家文化影响,这种文化强调“身体发肤,受之父母,不敢毁伤”。纹身被视为对身体的“损伤”,违反了传统道德观念。此外,儒家文化推崇克制和保守,认为外表的过度装饰或改变是一种“离经叛道”的行为,进一步加剧了社会对纹身的排斥。

3. 现代社会的观念转变与代际差异

随着全球化和文化多样性的增加,纹身在年轻一代中逐渐成为个性表达和艺术的一部分。然而,传统观念在韩国社会仍占据主导地位,尤其是在年长一代中,他们往往将纹身与不良行为、叛逆或社会不稳定联系起来。这种代际差异在电影中通过角色间的反应得到了体现。

4. 跨文化比较:纹身的全球视角

在西方国家,纹身更多被视为一种时尚、一种自我表达的方式,甚至在某些文化中象征身份、经历或精神信仰。例如,美国或欧洲的一些职业人士和艺术家将纹身视为个性和自由的象征。在韩国这样的集体主义文化中,纹身的接受度相对较低,因为它可能被认为是脱离群体规范的表现。

5. 影视作品对纹身的刻板印象加深

在韩国的影视作品中,纹身经常被用来塑造“反派”或“不良分子”的形象。这种表现手法强化了公众对纹身的负面联想,导致观众在现实中也更容易将纹身与危险或违法行为联系起来。

6. 纹身文化与法律的关系

值得注意的是,在韩国,纹身并不完全合法。根据现行法律,只有持有医师执照的人才能合法进行纹身操作。这种法规体现了社会对纹身的管控和谨慎态度,也进一步限制了其普及和被接受的程度。

结论

韩国社会对纹身的偏见不仅仅是历史和文化的产物,也是社会规范、法律与代际价值观的共同作用结果。虽然年轻一代正逐渐改变这种观念,但要完全消除纹身的负面联想,可能还需要时间以及对多元文化的更多接纳。

In the Korean movie Semantic Error, the characters' negative associations with tattoos, particularly linking them to "gangsters," reflect deep-seated biases and the socio-cultural context of South Korea. This phenomenon can be analyzed from several perspectives:

1. Historical and Cultural Context of Tattoos

Tattoos in South Korea carry a complicated historical background. Traditionally, tattoos were often associated with criminal organizations or marginalized groups. They served as markers of gang membership or loyalty to a group. This historical memory has imbued tattoos with negative connotations, making them incompatible with mainstream cultural norms.

2. Confucian Values on Morality and the Body

Korean society, influenced by Confucianism, emphasizes the idea that "the body is a gift from one's parents and should not be harmed." Tattoos are often seen as a form of "self-inflicted harm," which violates traditional moral principles. Furthermore, Confucianism promotes restraint and conservatism, viewing excessive bodily decoration or alteration as a deviation from social norms, thereby reinforcing societal aversion to tattoos.

3. Modern Shifts in Perception and Generational Differences

With globalization and increasing cultural diversity, tattoos are gradually being redefined among younger generations as forms of personal expression and art. However, traditional attitudes still dominate Korean society, particularly among the older generation, who often associate tattoos with delinquency, rebellion, or social instability. This generational divide is reflected in the reactions of characters in the film.

4. Cross-Cultural Comparison: A Global View on Tattoos

In Western countries, tattoos are more often seen as a fashion statement, a form of self-expression, or a marker of identity, experience, or spiritual beliefs. For instance, in the U.S. or Europe, professionals and artists alike use tattoos to symbolize individuality and freedom. In collectivist cultures like Korea, however, tattoos are less accepted as they may signify deviation from group norms.

5. Stereotypes Reinforced by Media

In Korean media, tattoos are frequently used to portray "villains" or "delinquents." This portrayal reinforces public stereotypes, making people more likely to associate tattoos with danger or criminality in real life.

6. The Legal Perspective on Tattoos

It is worth noting that tattoos in South Korea are not entirely legal. Under current law, only licensed medical professionals are allowed to perform tattoo procedures. This regulation reflects societal caution and control over tattoo culture, further limiting its acceptance and normalization.

Conclusion

The prejudice against tattoos in Korean society is not only a product of historical and cultural factors but also the result of social norms, legal frameworks, and generational values. While younger generations are gradually challenging these perceptions, it will likely take time and greater cultural openness for tattoos to shed their negative associations entirely.

本文由

中外文化交流

提供,采用 知识共享署名4.0

国际许可协议进行许可

本站文章除注明转载/出处外,均为本站原创或翻译,转载前请务必署名

最后编辑时间为:

2024年12月11日